Slán go fóill

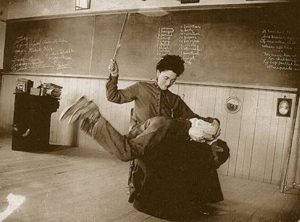

Chief among my tormentors was my Irish teacher, Miss McGovern, a volcanic disciplinarian who ate little boys like me for breakfast. She unleashed her entire armoury upon my sullen soul. Everything from laps round the school, to lengthy kneeling sessions (this was the 1990’s) and daily detentions were trialled in a futile attempt to tame me. At one point, having relocated me to the front of the classroom, to a seat beside the meekest, best-behaved child in Ireland, and a corner all to myself, she instructed me to join her at the top of the class, behind her desk.

This arrangement, like all the others, didn’t work out. Eventually I was downgraded to a lower stream. But not before I tried a few tricks of my own. I’d heard that, under the right circumstances, I could be exempt from Irish, that if I’d started my schooling abroad, came late to the game, I could wave goodbye to As Gaeilge and Miss McGovern. I had started my schooling abroad, coming to Ireland at the age seven after two intensive years in a Lancashire comprehensive. This was all the ammunition I needed. Those two lost years were clearly the problem. I’d never stood a chance.

There it remains, occasionally spurting forth unprompted; ‘tá mo chroí i mo bhéal’, ‘is maith liom cáca milis’, and other helpful phrases still linger, all of which will stand me in good stead should Sinn Féin ever take over the country and ban the use of all but the mother-tongue. Because they love Irish, don’t they? Look through the names of their TDs and councillors, it’s like stepping back into the land of druids and magic dogs, there’s more fadas than the proclamation itself. They even use it in their speeches, signing off with a flourish, tiocfaidh ár lá, our day will come. And maybe it will, maybe with Gerry out of the picture they can finally erase the sins of the past.

Right now though they’re mostly concerned with showing everyone how much they love Irish. Their efforts to introduce an Irish Language Act in the North are somewhat bizarre, a move designed to appease their southern constituents and remind us that they, and they alone, are the only party truly committed to returning the country to its former unified glory. Because Northern Ireland is Irish in name alone; the notion of having bilingual road signs, of Irish being spoken in their assembly and taught in their schools, is but a fallacy and a dangerous one at that; one capable of adding fuel to a fire that never goes out.

This peculiar love affair has manifested itself in recent years with a rise in Gaelic-sounding baby names. Where once we were a country of Pats and Conors, a simple people just trying to get by, we’re now a mighty race of Ultans and Cearbhalls, a fearsome tribe who could just don some paint and invade Normandy if the mood happened to take us. However, if any of us found ourselves stranded in the Gaeltacht, if the car broke down and we were forced to commune with the locals, we’d splutter and mumble our way through a few cursory phrases, before begging them to speak the Queen’s English like the good buachaills they are. We firmly believe that Irish should be maintained and that it’s an important part of our heritage, but only if someone else keeps it going, and we don’t have to speak it.

From a cultural perspective it’s nice that it’s still spoken, it ties us to the past, helps make sense of our chaotic history. It reminds us that we are Irish, that we’re a bit different, that they could never keep us down. But looking at it from a dispassionate perspective, Irish is of little worth to us, being able to speak it is cute, a nice string to have to your bow, but about as useful as Latin or Klingon. Unless you plan on becoming an Irish teacher or joining TG4 then there’s no real reason to persevere with it once you finish your Leaving Cert. In fact, now that religion has finally been ousted from the syllabus, maybe it’s time another redundant, mostly pointless, subject was removed too.

I know what you did last summer

In such circumstances there’s not a whole lot you can do, it’s simply a case of keeping your head down and trying not to cry into your computer every time they walk past. There is one other option though, a way of alleviating the hurt, at least temporarily. You could look them up on social media, trawl through their pictures, find a suitable snap, of them on a beach, perhaps scantily clad, and profess your love for them privately, in the comfort of your own home.

A survey has revealed that 39 per cent of men masturbate to the Instagram photos of their work colleagues. Yes, I know, disgraceful, shocking, degenerates to the last. But wait, hold on just a second, because 42 per cent of women admitted doing the same. Interestingly, 51 per cent of women believed that their colleagues had used their pictures for this purpose, while only 21 per cent of men were conceited enough to think that their topless shots from Magaluf had made it into someone’s greatest hits list.

So, what does this tell us? Well, for a start, it appears that women are equally, if not more, perverted than men. As if that wasn’t bad enough, you’ve also got bigger egos, a level of hubris which dwarfs that of the humble male. You may argue that this survey can’t be taken seriously, that there were only two thousand respondents, not nearly enough to accurately reflect your late-night proclivities, but I’m afraid the game’s up lads, you’ve been rumbled. Now if you don’t mind I’m off to take down those pics of me in my shorts, can’t be too careful nowadays.