The meat grinder

If you’d been on Twitter last week you’d have been convinced that there’s no real need for the Leaving Cert at all. People of all ages, all professions, were falling over themselves in their efforts to discredit our state exams, offering all sorts of sage advice as they humbly bragged about overcoming terrible results to achieve fame, greatness and world domination. On the surface it appeared that the intention was to allay the fears of those who did badly, to provide solace and consolation, hope for the future.

If you’d been on Twitter last week you’d have been convinced that there’s no real need for the Leaving Cert at all. People of all ages, all professions, were falling over themselves in their efforts to discredit our state exams, offering all sorts of sage advice as they humbly bragged about overcoming terrible results to achieve fame, greatness and world domination. On the surface it appeared that the intention was to allay the fears of those who did badly, to provide solace and consolation, hope for the future.

But really this was all about them. Because their stories, as inspirational as they were, are of little relevance to those who’ve just received their results. The alternate pathways of a decade ago, of even five years ago, have long since shut. The ever-evolving Irish economy closes as many doors as it opens in any given year.

And, despite what they say, despite them prophesying about the future, predicting sunny days and happy lives, they’re mostly talking out of their backsides. Because although it’s not quite the end of the world if you do badly in your Leaving Cert, it’s not far off it.

For every one of those success stories on Twitter, every one of those people who laughed in the face of the Leaving and ploughed their own magnificent furrows, there are dozens who discovered that life becomes incredibly difficult if you leave school without the right credentials.

At the risk of contradicting myself, of making this all about me, I might just share my own post-Leaving Cert experiences. By doing so I may provide a more accurate reflection of the life of an underachiever, inject a dose of reality into a debate which is imparting only one kind of wisdom upon those listening, portraying the world as one big fairy tale with not a monster or a wicked witch in sight.

From there I got a job in a supermarket, then a job in a garden centre, a call-centre, a factory, another factory, I did a computer course, tried another call-centre, before somehow ending up here. You might say that all’s well that ends well, that my years in the wilderness provided valuable life lessons, a taste of the real world, but I’d rather not have had those lessons, tasted that world. I’d have much rathered if someone within the educational system had cottoned on to the fact that, in spite of my academic inertia, I possessed at least some of what’s required to make a half-decent journalist.

The reality is that I’m incredibly lucky to have found something I enjoy doing, even at this late juncture. In another time I would have stayed in one of those other jobs, seen out my days doing something I despised, and been none the wiser. But even now, I look at those years, that lost decade, and wonder what might have been. I wonder how I’d have fared if I’d got into my profession of choice at a younger age, how my career might have panned out if I’d graduated in my early twenties instead of my thirties, and how my life would have been oh so different if I’d had a decent Leaving Cert.

Because that’s the crux of the issue; better results would have led to a better life, a happier life. And for all the sermonising on Twitter, all the heroic tales of defying the odds, the same is true today.

The Leaving Cert is the first piece of social capital a young Irish person can acquire. A good one earns you respect, a place in college and a myriad of opportunities. A bad one, a below-par one, can make you feel worthless, ignored and discarded, consign you to a lifetime of frustration and regret.

So it does matter, it matters a hell of a lot. But should it matter, and should it even exist?

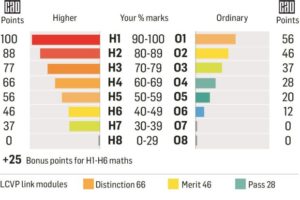

A lot has been made of the new points system and the reform to the grading scale, but nothing appears to have changed. School leavers are still being penalised unfairly, denied college places for failing irrelevant subjects. Like the four thousand students who failed maths, and as a result, effectively failed their Leaving Cert. They may be gifted in other subjects, be skilled in English, history and geography, but because they can’t tell their Pythagoras from their Pi they’re prohibited from fulfilling their potential.

You may balk at the suggestion that maths could ever be classed as irrelevant, but what use is algebra to someone who wishes to study English literature?

The German way of doing things is often cited in this instance, and with good reason. Rather than force their youngsters to toil away at subjects they’ve struggled in since day one, it allows students to narrow their focus from a young age, using the recommendations of teachers to streamline them towards careers they’ve shown an aptitude for. It doesn’t rank kids or use crude points’ systems to decide who’s the best. Instead it carefully guides each individual down structured, tailor-made paths, avenues of study which are specifically designed for students with their abilities. For proof of this system’s efficacy one need only look at the perpetually thriving German economy.

Upon reflection, those people on Twitter were at least half-right. There isn’t any need for the Leaving Cert, at least not in its current guise. There’s no need to make teenagers study subjects which they have no interest in and which won’t have any bearing on their future careers. What there is a need for is to treat them as individuals, to recognise their unique abilities, and to stop feeding them into this meat grinder year after year.

I could do so much better than you

To further confuse matters, a study carried out by behavioural scientists has revealed that when pursuing a mate we, on average, target someone who is 25 per cent more desirable than ourselves. Using data from an unnamed dating site, researchers measured desirability by the number of messages a person receives and the desirability of those sending them. How people were listed as desirable in the first place was down to the website itself.

Essentially this study proves that we’re all a bit deluded when it comes to finding a potential partner. Rather than remain realistic and aim low, we choose to ignore our shortcomings, believing that if only that nine out of ten with the doctorate from Trinity could get to know us they’d be smitten. We forget that we could do with losing a few pounds, that we still live at home with our parents, that the last time we had sex the other person fell asleep during it, and focus entirely on their lovely smiley face and how nice it would be to kiss it.

Meanwhile, as we bombard them with messages, our excitement growing with each bored response, the object of our desire is sending some messages of their own. Because, despite being a nine out of ten, being an absolute thunder-ride, they want someone who’s 25 per cent more desirable than them as well. They want a ten out of ten, someone with two doctorates, a yacht and a Ferrari. But, until they find that person, you’ll just have to do.