The recently opened Molecular Laboratory at University Hospital Limerick (UHL) has boosted the hospital’s already significant COVID-19 testing capacity, and provides the potential, post-pandemic, to increase the scope of molecular testing in infectious diseases.

With a total project cost of approximately €4m and funded as part of the national pandemic response, development work on the laboratory commenced last autumn.

Since opening earlier this year, COVID-19 testing capacity in the hospital has risen by 50%, increasing by approximately 200 tests per day the hospital’s previous daily test capacity of approximately 400-450.

And the new laboratory’s Whole Genome Sequencing capacity, with its ability to detect SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOC), such as the Delta variant of the virus, and track outbreaks in a more accurate and timely manner, could position UHL as an important element in the national response to calls from the European Centre for Disease Control for tracking COVID-19 and its multiplicity of viral lineages.

Dr Patrick Stapleton, Consultant Microbiologist, explained that the rapid testing capacity for COVID-19 and the Whole Genome Sequencing capacity, are housed in a purpose-built facility that has been developed to the highest possible standards.

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing of nasal and throat swabs is considered one the most sensitive tests available for SARS-CoV-2. It includes four distinct phases, sample preparation; extraction (the release of viral genomic material from the sample); amplification (exponentially increasing copies of target viral genome to facilitate detection); and analysis of the results prior to reporting as detected or not detected.

The laboratory team worked closely with HSE Capital and Estates to optimise this design of the state of the art Molecular Laboratory.

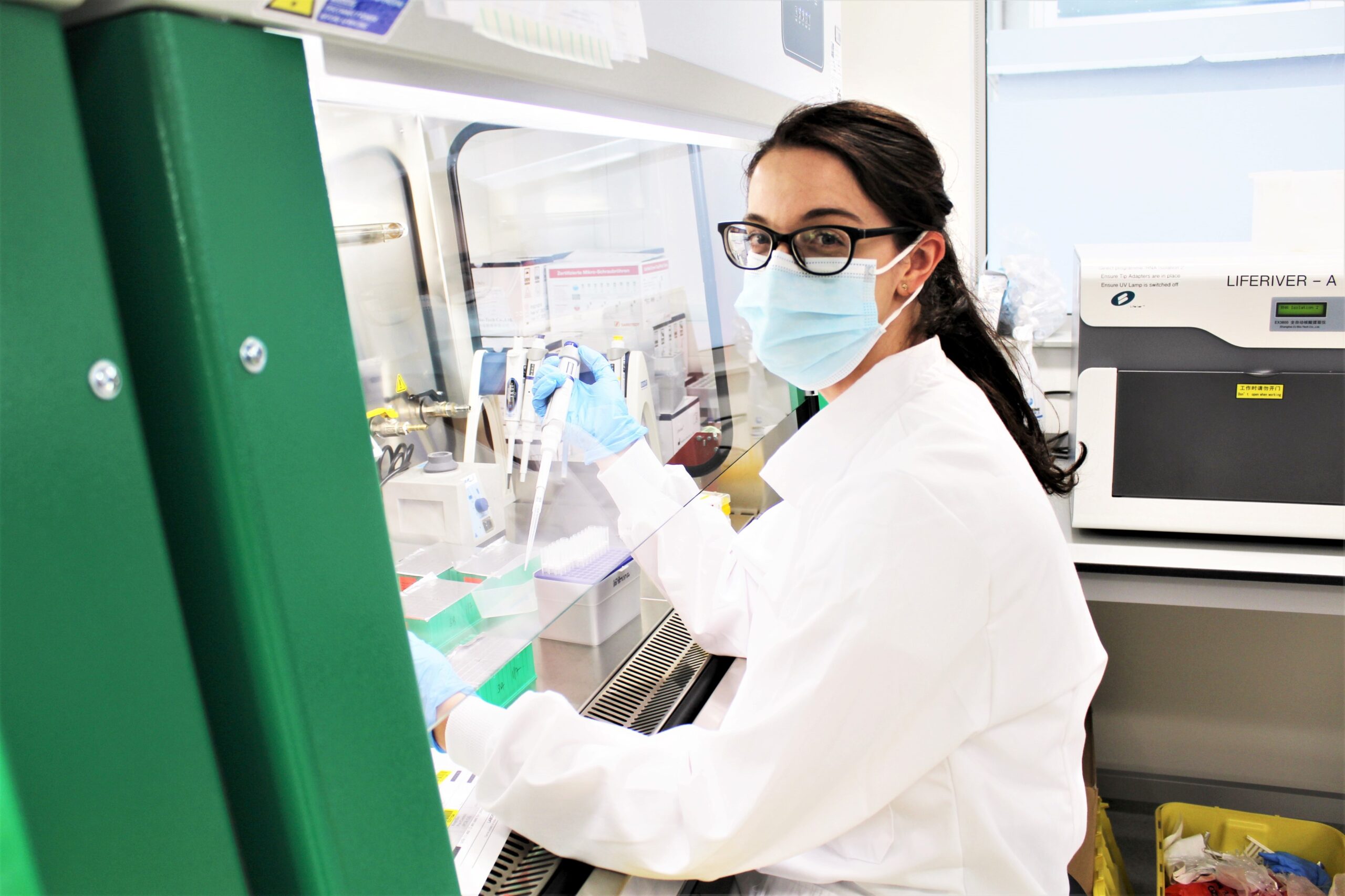

Colm McDonnell, Chief Medical Scientist, explained that: “for the most accurate results and to avoid any potential for cross-contamination, separate work areas in the laboratory were dedicated to each phase of the PCR testing process, with separate air pressures designed to extract any potential contaminants from other areas. Each area has dedicated lab coats and equipment.”

UHL has one of Ireland’s busiest hospital COVID-testing services, Dr Stapleton explained.

“Prior to the opening of the molecular lab, our serology and microbiology laboratories, supported by all lab disciplines, had already built that capacity from scratch, and we were delivering fast, accurate test results for people attending our hospitals, and for people in the local community. However, the new Molecular Lab enhances this with permanent facilities, designed to ensure that we have best possible practices, procedures and environments in place to prevent any contamination of samples,” Dr Stapleton said.

The building, which stands on a site to the rear of the hospital campus, is connected to the hospital’s pneumatic chute system, which not only shortens the turnaround time of transporting samples to the laboratory, but also minimises footfall throughout the hospital building.

With all COVID-19 testing equipment moved to the Molecular Lab from its temporary home in the laboratory of the Clinical Education and Research Centre (CERC), UHL’s COVID-19 testing capacity is now under one roof, and is composed of the high throughput Abbott ‘Alinity M’ diagnostic instrument, a fully automated sample-to-result system; the Serosep RespiBio testing platform; and the GeneXpert and Luminex Aries testing platforms which provide random-access rapid test capacity as a complement to fixed daily runs of batch PCR tests.

With PCR test capacity now complemented by Whole Genome Sequencing, Dr Stapleton says that the new Molecular Laboratory has “huge potential” as a centre of molecular diagnostics, across all laboratory disciplines.

The WGS instrument in the UHL laboratory, the Oxford Nanopore MinION, operated by specialist scientist Dr Carolyn Meaney, is smaller than a child’s tablet. With a capacity of 12-96 samples per week, it can not only efficiently detect the virus, but also traces its lineage, and provide even more detailed analysis, such as individual mutations within a virus strain, which can then be used by outbreak control teams to track the spread of outbreaks.

Dr Stapleton represents the Irish Society of Clinical Microbiologists on the steering group of the National SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance and Whole Genome Sequencing Programme. Looking beyond the pandemic, he says that WGS has “a wealth of applications” beyond COVID-19, and could be used to investigate outbreaks of most other diseases. He also foresees its potential for helping to diagnose cancers and identify the treatments that are likely to be most effective.

In addition to enhancing the efficiency of UL Hospitals Group’s outbreak control teams, the PCR and WGS diagnostic capacity of the Molecular Lab has obvious potential for public health across the region.

“It is very exciting to watch these things come to fruition. Whole Genome Sequencing is now where molecular diagnostics was at 20 years go. It is currently moving out of the academic laboratories and into the clinical laboratories. And it’s in this transition from the academic labs, and into working molecular diagnostic labs in clinical spaces, like this one—that’s the key to maximising benefit for patients, and get it working for patients,” Dr Stapleton said.