RECENT calls for expansion at Dublin Airport, namely the removal of the 32 million cap on passenger numbers, are at odds with key national strategic policies and fail to recognise the opportunity that exists to utilise existing infrastructure and capacity within the state’s airport network.

Today, Ireland stands as an outlier in terms of the concentration of air traffic at just one of its network of airports, with Dublin Airport accounting for 85 per cent of passenger traffic and the remaining 15 per cent spread across the country’s other five regional airports.

When one considers that almost 40 per cent of the population reside in Munster and Connacht, the lack of balance is clear.

Across Europe, Dublin Airport is a clear outlier with such a high proportion of national traffic travelling through one airport.

Take, for exmaple, Schiphol in Amsterdam, which was once top of the pile in terms of overconcentration. The Dutch Government capitalised on the opportunity to cap aircraft movements at Schiphol in a bid to manage the negative impacts associated with such a highly concentrated market share.

Recent commentators on the debate suggested this hadn’t worked for other Dutch Airports, with flights deciding to redirect outside the Netherlands. While this may be true to some extent, data suggests that whatever the Dutch Government is doing is working.

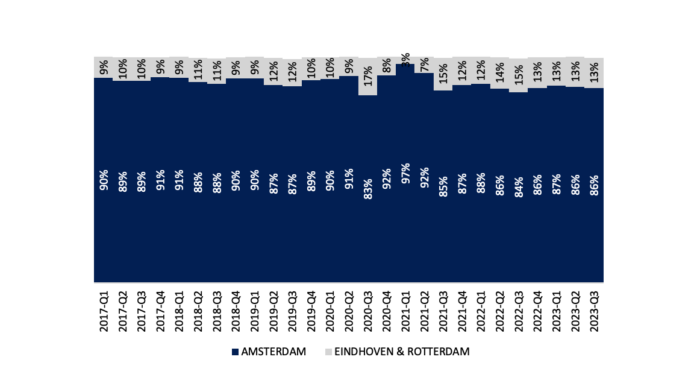

At the beginning of 2017, Amsterdam accounted for 90 per cent of all passengers into the Netherlands, with Eindhoven and Rotterdam accounting for just 9 per cent. By 2023 Amsterdam’s share had decreased to 86 per cent, while Eindhoven and Rotterdam increased to 13 per cent of total passenger share.

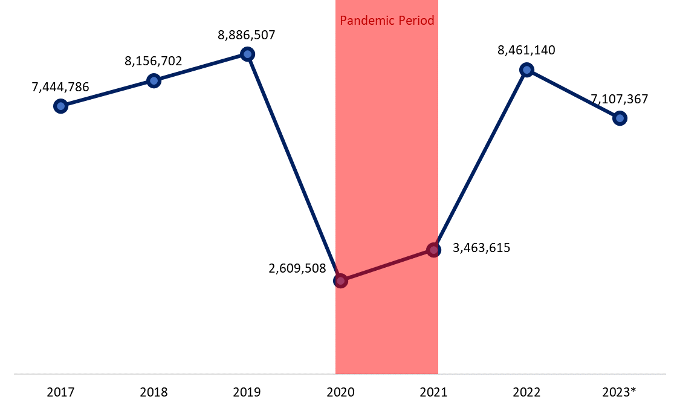

While these numbers might seem small in percentage terms, they are far from small in passenger terms with numbers at Eindhoven and Rotterdam increasing by 700,000 per year in 2019 and 2020 – indeed if it wasn’t for the pandemic, we would be able to fully examine the proper impact of Dutch Aviation Policy.

Of course, Amsterdam continued to grow but at a much slower pace than the years prior – average year-on-year passenger growth for 2016 and 2017 was 8.5 per cent, meanwhile the following two years the average growth was 4.7 per cent.

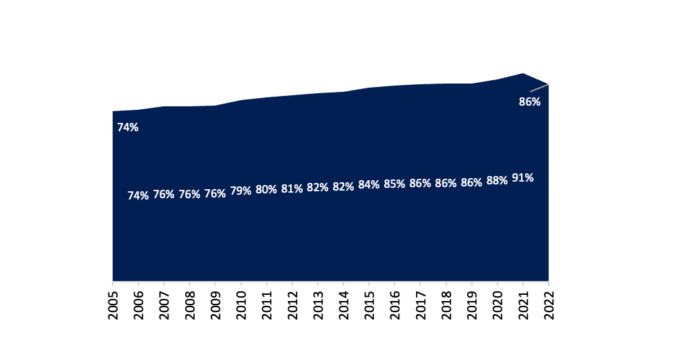

While Dutch aviation policy has aimed to redistribute growth outside Amsterdam, Irish aviation policy (or lack of) has not had the same goal on native soil. The share of passengers and overconcentration at Dublin Airport has continued to increase over time. From a low of 74 per cent in 2005 up to 86 per cent in 2022.

Decisions by successive Irish governments as well as regulators and planners to support the continued expansion of Dublin Airport have contributed to the current concentration of air traffic at the airport.

The result, growing congestion at the airport, significant pressures on the surrounding transport network, concerns for the health and wellbeing of those living in the vicinity of the airport, whilst at the same time limiting the ability of the country’s other regional airports to operate on a more sustainable basis.

Project Ireland 2040 is the Government’s overarching strategy for the State, with a firmly articulated vision for achieving balanced regional growth. Key to realisation of this vision is a more even distribution of economic growth including to the second-tier cities of Galway, Limerick, and Cork. Regional airports have a critical role here. The relationship between access to air connectively and attracting foreign direct investment, facilitating indigenous industry expansion/exports, and driving regional tourism growth, is well documented.

Instead, the current concentration of air services in Dublin, which requires passengers to travel across the country to avail of services, and could feasibly be served closer to home thus increasing the possibility of more sustainable journeys through a shorter commuting time, is adding significantly to the cost of both business and leisure travel, with additional negative environmental impacts and costs.

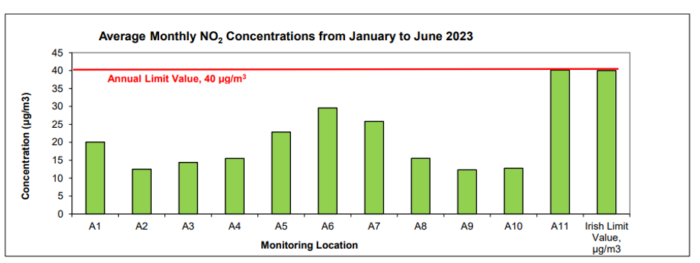

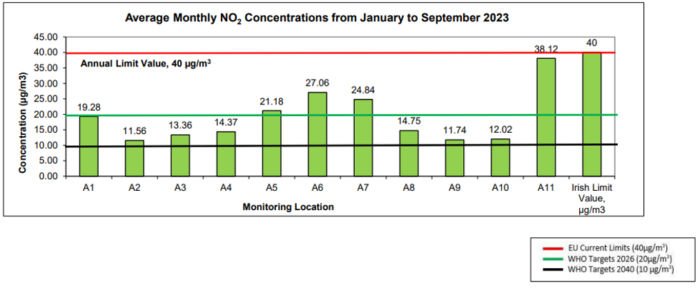

Indeed, the level of bus connections to Dublin Airport is such that airport’s Air Quality Monitoring data for Q2 2023 shows that the level of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) at the bus depot at Dublin Airport (A11) was at its annual limit 40 µg/m3, however this has since decreased to just under the limit at 38.12 µg/m3.

To put these figures into perspective, the WHO targets by 2026 are 20 µg/m3 and by 2040 are 10 µg/m3.

Both the Climate Action Plan and the Government Strategy on the Circular Economy articulate the need to optimise existing infrastructure, rather than continually developing new infrastructure. All five regional airports in Ireland have under-utilised capacity. In line with the direction set out in these key national policy documents, the focus now must be on maximising the use of the nation’s existing airport infrastructure. For example, Shannon Airport has additional capacity for around three million passengers.

Market dominance of Dublin Airport also poses risks for the resilience of the economy as a whole. Where a country has an excessive reliance on a single airport, similar to the situation in Dublin, any disruption caused, for example by natural disasters, technical failures, or related to labour shortages, can have hugely adverse impacts on the economy. A more balanced spread of capacity across the national airport network will reduce the impact of any such disruptions.

Shannon Airport has the longest runway in the country, which is capable of handling any type of aircraft and also of operating 24/7 without noise restrictions.

The airport also offers US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities. It has the largest terminal capacity outside of Dublin Airport, with large, segregated arrival, departure, and transit lounges and 41 check-in desks.

Given the scale of the terminal and airfield infrastructure, it also has potential for future growth without the need for significant infrastructure investment.

The location of Shannon Airport means it can serve as a key economic driver for the cities of Galway, Limerick, and Cork and the wider regions in the west of Ireland.

Currently, however, government policy is not supporting the airport. The level of public transport for example serving Shannon Airport is dismal. On any given day, whilst there are 34 and 11 private coaches from Galway and Cork respectively serving Dublin Airport, Shannon Airport has no direct intercity services from Cork or Galway.

If the State is serious in its ambition of achieving balanced regional economy, it is essential that the expansion of Dublin Airport does not continue unchecked, and that the capacity of regional airports is utilised, optimised, and developed further. Government policy makers, planners, and regulators must take action and put in place measures in this regard.

The government must expedite a full review of the National Aviation Policy to ensure that it aligns with Project Ireland 2040 and the Climate Action Plan.

In tandem, government must look at wider transport and tourism policies. If we are serious about supporting balanced economic development and achieving our climate action targets, more direct bus services from the cities to regional airports including Shannon Airport must be delivered.