A STARVING Limerick grandmother who has been on hunger strike for more than a month was told by the Minister for Education that “nothing is on the table” regarding future redress or support measures for survivors of industrial and reformatory schools.

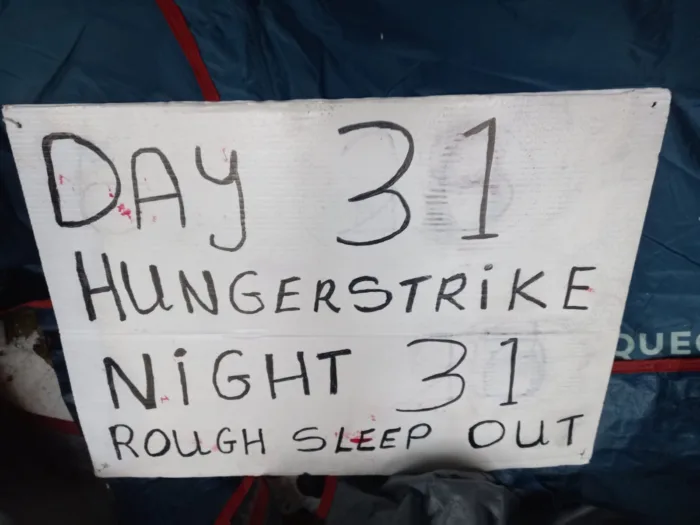

73-year-old Mary Dunlevy Greene from Kilteely is one of four sleeping rough and on hunger strike outside the Dáil since late September.

Mary was sent to Mount St Vincent Industrial school in Limerick, now the John Henry Newman Building at Mary Immaculate College, just two weeks after her fourth birthday.

Her mother died during childbirth just six months previous, leaving behind five children and her husband, a farm labour, who came home one day to find his children no longer there.

On the 10th day of the groups hunger strike, the starving demonstrators were asked to meet with Education Minister Helen McEntee in Buswells Hotel in Dublin.

Speaking to the Limerick Post from the tent she has been rough sleeping in for over 31 days now, Mary says another member of the group, Maurice Patton O’Connell, asked the Minister what was on the table for survivors regarding retribution.

According to Ms Dunlevy Greene, the response from Minister McEntee was “there is nothing on the table”, and told the group she only met with them upon their request.

“She got into her chauffeur driven car outside the steps as we were sitting there contemplating what had happened,” Mary recalled.

In a statement to the Limerick Post, a spokesperson from the Department of Education said that they are “very conscious of the enormous trauma which has been experienced by all survivors of abuse.”

“The Minister met with the survivors concerned on Monday 29 September, to hear from them personally. An Taoiseach also met directly with members of the group on Friday 3 October. At each of these meetings concern was expressed for the survivors’ physical and mental health as a result of their decision, and they were asked to reconsider it and to engage with officials in relation to the matters that they have raised. The Minister has also written to the group on a number of occasions to outline the position”, the statement read.

The statement also outlined engagement between the Department of Education and Youth and members of the group over the past number of years, most recently in August when Department officials travelled to Limerick to meet directly with the group and listen to their concerns.

Helen McEntee is urging the group “to act in the best interests of their health by ending their protest, and reiterates that officials remain available to engage with the group.”

Reflecting on her time at Mount St Vincent’s, Mary said the school “took every human right” away from her, describing it as a place where she “got very little food, from the time we got up until it was time to go to bed, it was work, work, work”.

“You would scrub and clean the floors, clean the church, and every part of the institution.”

“We didn’t even have basics like a toothbrush or face towel, and we never saw our own reflection in a mirror,” she added.

Mary and three other protesters, Miriam Moriarty Owens, Mary Donovan, and Maurice Patton O’Connell are calling on the government to introduce universal medical cards and a State contributory pension for survivors of industrial and reformatory schools.

“We never got any medical attention as children. If we were sick, we were put upstairs in a little room with three beds in it and we could be forgotten about for days. We wouldn’t be fed or watered, and never saw a doctor or a dentist,” Mary told the Limerick Post.

“Any medical issues we have at this stage are all due to the lack of care during these years when every part of our body was still being formed. We were only babies but we were doing hard labour.”

The decision to go on hunger strike was not made lightly, Mary explains, adding that the group “did their homework and the impact it would have on their bodies before we started”.

The Limerick woman says her “body is getting weaker, but our determination is getting stronger because we owe it to the 4,000 living survivors out there”.

“I’ve never slept in a tent in my life and I’ve never wanted to either, but I’ve spent the past 31 nights here now and it’s cold, and it’s hard repeating your truth every day because people are completely unaware of the industrial schools.

“It’s part of our history, it may be dirty, but it can’t be sanitised, the truth has to be put out there.”

Mary, now a mother of three and grandmother to six, said her family was left “fractured” after being torn away from one another as children.

“I met my brothers, who were in a school in Cork, later in life and we were more acquaintances than siblings because we never grew up together,” she said.

She also recalls the longest conversation she had with her father just two weeks before he passed away.

“I asked him why he never married again or settled down and he said he couldn’t potentially go through the same thing again. He was only 31, and I think he died a broken man,” she said.

Mary and the rest of the group have vowed to continue with their hunger strike for as long as it takes.