ON May 21, 1873, Eleanor McGhie sat down at her writing desk at 56 William Street to pen a letter to her niece Mary Mossop in Philadelphia. Eleanor was not the quickest at corresponding as her opening line reads, “It is now nearly three months since I received your kind letter.”

She then thanked her niece for the Valentine sent in February to her daughter Annie. The excuse Eleanor gave for her tardiness was that she “had no servant for nearly four months so I am kept busy.”

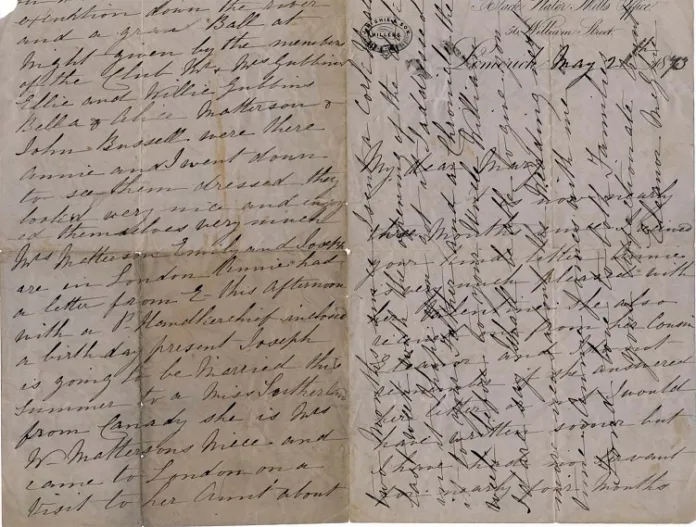

To make up for the delay, she gave a long, detailed response on one sheet of paper folded in half. She wrote on all four sections of the folded sheet and having filled them she returned to the first page again. This, she rotated by 90 degrees and began to write over the initial lettering.

This method was known as ‘cross writing’ and was common practice during the Victorian era when postage was still charged by the page, and writing paper was expensive. Occasionally letters were even re-crossed, turning the page 45 degrees and cross writing once more. In this fashion, several pages could be written onto one sheet, although in many cases this would render the letter almost illegible.

Eleanor McGhie’s letter was still quite clear and concise. Along with the trivial information on family members’ wellbeing, the letter also gave a brief glance into the life of a Limerick woman in the 1870s.

The author was born Eleanor Mossop on October 23, 1823 in Cumbria, England. Her link to Limerick began when her aunts, Mary and Eleanor Mossop, married Joseph Matterson and John Russell respectively.

These men arrived in Limerick in 1816 to establish the Matterson’s bacon factory. By the 1830s the surviving Mossop brothers, which included Eleanor’s father John, joined the sisters in Limerick.

Eleanor married James McGhie, a miller whose family ran the Blackwater mills. Their office and her home was at 56 William Street, the address from which Eleanor’s letter was posted. She had one child, a daughter, Annie McGhie born May 19, 1862, in Limerick. Tragedy struck the family, only a year later when her husband died.

As the wife of a miller, she was considered a station below her Matterson and Russell relatives and although she would have been privy to many of the social events in Limerick, she may not have received an invitation.

In her letter she refers to the recent visit of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, John Poyntz Spenser, to Limerick to open a new gravel dock. On arriving in Limerick in the afternoon of Tuesday May 13, 1873, the Lord Lieutenant took luncheon at the residence of James Spaight on Georges Street. At three o’clock he arrived at the dock which was officially opened with a speech by the Harbour Commissioner.

The Lord Lieutenant rose to make his speech but was interrupted by the jeers of a large crowd which had gathered to demand the release of political prisoners, and the return of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

O’Donovan Rossa, the founder of the Phoenix Society, which would later be incorporated into the Irish Republican Brotherhood, was exiled from Ireland and travelled to New York in 1871. This riot would go no further than a vocal display as the ceremony had also been attended by military. The rest of the ceremony went off without a hitch.

Following the ceremony, the Lord Lieutenant and his wife were lead to the Model School, where they were welcomed into the boys’ room with a rendition of ‘God save the Queen’. Proceeding to the girls’ room, two copy books, including that of Eleanor McGhie’s 11-year-old daughter Annie, were inspected and duly complimented upon, the Countess stating that “they were very nicely written”.

Following other spectacles and displays Annie McGhie and two of her classmates were once again called upon this time to recite ‘Lady Clare’ – a poem written by Alfred Lord Tennyson, who was poet laureate at the time, making this piece quite contemporary.

On the Wednesday, a ball was held in honour of the Lord Lieutenant at the Limerick Country Club. Eleanor and Annie McGhie, although not in attendance, enjoyed much of the mood and revelry as their relations, the Matterson, Russell, and Gubbins families, prepared for the evening. The ball would last until two the following morning, after which the Lord Lieutenant rose at 9am that day and made the short journey to fish at Doonass before returning to Dublin by train from Castleconnell station.

Eleanor concludes her letter with the following light hearted family mentions and well wishes:

“Mrs Matterson, Emily, and Joseph are in London. Annie had a letter from E- this afternoon with a P-handkerchief enclosed, a birthday present. Joseph is going to be married this summer to a Miss Sutherland from Canady, She is Mrs W Matterson’s niece and came to London on a visit to her aunt about two months since. I sent a Cork Herald last week with the opening of the dock in it, I hope you get it. I addressed it to your father and a Chronicle the week before to your uncle William. I dare say I shall be able to give you more news about the wedding next time. Annie joins me in fond love to both families.”

Eleanor McGhie lived until 1912, at almost 90 years old she saw the entirety of the Victorian era in Limerick. The life of the Protestant middle classes in Limerick would alter completely within 10 years with the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence and Civil War.